No work better embraces narrative medicine than A Short Life, by Jim Slotnick. This prescient memoir, written in 1983 and published in 2014, narrates a young medical student’s terminal illness from pre-diagnosis to his final days. It is a song of life’s joys, deadly shortcuts in medical practice, the necessity of listening and paying attention, and the essential value of compassion.

Read moreThe Skin Above My Knee: A Memoir by Marcia Butler

When was the last time you really, truly listened to music? In the rush-rush of daily life, it's not always easy to sit, close your eyes and listen—deeply, emotionally, exclusively—to, say, a Mendelssohn Violin Concerto or "Naima" by John Coltrane or even Adele's achingly nostalgic love song, "Hello." Instead, we OM at a meditation class, zone out watching "The Crown" or "Black Mirror," or catch up on the latest Intima Field Notes (sorry, a bit of shameless self promotion) to de-stress from our chaotic lives. We often forget the restorative, soul-enhancing powers of music, the way we can lose ourselves and discover other worlds and emotional depths when we focus and attentively listen.

During her 25-year musical career, Marcia Butler performed as principal oboist and soloist on renowned New York and international stages, with many musicians and orchestras, includin pianist Andre Watts, composer and pianist Keith Jarrett, and soprano Dawn Upshaw.

Those feelings came rushing back to me as I read a new memoir by Marcia Butler, entitled The Skin Above My Knee. Butler, who published a story called "Cancer Diva," in the Spring 2015 Intima, was a classical oboist in New York City for 25 years. She has written an extraordinary and moving account of her life that goes beyond stories about her difficult childhood, icy and aloof mother, the many abusive men in her life and her struggles with addiction. Yes, we get all of those painful stories, fleshed out and delivered with Butler's sensitive, yet sardonic wit, but we also are party to her love and mastery of music.

Oh, glorious music! Every other chapter or so, Butler brings her musical world to life in palpable detail, pulsing with all of its highs, lows and endless hours of practice. We see her pride and excitement about being accepted to a music conservatory on full scholarship only to be told to play nothing but long tones "for months, possibly till the end of the semester." We watch, as she learns the "hell" of crafting the perfect reed from scratch only to ruin it and start all over again. We accompany her through the nerve-wracking challenges and transcendental joys of performing.

Consider this short excerpt where she describes accepting an invitation from composer Elliott Carter to be the first American to perform his oboe concerto:

Upon receiving the score, you can't play the piece or even do a cursory read-through. This is an understatement. You can't play a single bar at tempo or, in must cases, even three consecutive notes. You have to figure out how to cut into this massive behemoth. First learn the notes. Forget about making music at this point. Just learn the damn notes. Your practice sessions consist of setting the metronome at an unspeakably slow tempo and then playing one bar over and over until you can go one notch faster.....

...You remember the exact passage when the cogs lock together. It is not even the hardest section, technically, but what you begin to hear is music. There's music in there, and it is actually you making that music. Your stomach rolls over, a love swoon. The physical sensation is visceral and distinct. It is a very private knowing: a merging with something divine, precious, and rare. As a musician, you covet those moments. You live and play for them. It is a truly deep connection with the composer, as if you channel his inner life. A tender synergy is present, and you fear that to even speak about it will dissipate it immediately. Don't talk. Just be aware.

We're fortunate that Butler has decided to talk about her intense love affair with music and share her most intimate moments with us in this entertaining memoir. While the author touches upon her cancer diagnosis briefly, this isn't an illness narrative in any way, shape or form. Yet, she brings the idea of attentiveness and deep focus to light through her musical calling and finds a way to counteract trauma and pain in the expression of her art. By opening up the conversation about difficult moments and learning the discipline to recognize, express and find meaning in them, Butler also reminds us to listen, deeply, to the music of the world around us, as dissonant, lilting, strident or soothing it might be. Find the music that personally delivers meaning to you, be it a concerto or Ed Sheeran, "Shape of You." For her, it was always Norwegian opera singer Kirsten Flagstad performing Isolde's final aria, the "Liebestod," in Richard Wagner's magnificent Tristan and Isolde.—Donna Bulseco

If you would like to hear Marcia Butler in concert, the author provided a link to work where she performed. Click on the title of a piece for oboe and piano, entitled "Fancy Footwork" from the album, "On the Tip of My Tongue" by composer Eric Moe.

DONNA BULSECO, M.A., M.S., is a graduate of the Narrative Medicine program at Columbia University. After getting her B.A. at UCLA in creative writing and American poetry, the L.A. native studied English literature at Brown University for a Master's degree, then moved to New York City. She has been an editor and journalist for the past 25 years at publications such as the Wall Street Journal, Women's Wear Daily, W, Self, and InStyle, and has written articles for Health, More and the New York Times. She is Managing Editor of Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine, as well as a teaching associate at the School of Professional Studies at Columbia University.

When Breath Becomes Air

It is often startling and unsettling to read the work of a writer who has passed. In some ways, this is the norm—it’s rare that students in school read books by writers still alive. The distinction, however, is this: those writers—Shakespeare, Joyce, Woolf, even Salinger, who only passed a few years ago—aren’t writing about their descent into death as they lived it. Paul Kalinthi’s When Breath Becomes Air details the last year of his life as he, a neurosurgeon, fights metastatic lung cancer. It sounds depressing in summary, though the book lacks any trace of self-pity or of anger. It is written with intelligence and with honesty, a product of reflection and insight. We can trust him, the reader knows, to present his story to us the same way we could have trusted him to operate on our brains. His humanity is tangible.

The most striking observation about the book is its voice. Despite his death last year, Kalinthi’s voice is rich and alive on the page, and he speaks not to doctors or to cancer patients but to anyone who is interested in the question of what it means to live and to die with humanity. Kalinthi spent his life devoted to this question, always torn between a career in the humanities and one in medicine. He ultimately pursued both, first a Master’s degree in literature and then medical school for neurosurgery. “The call to protect life—and not merely life but another’s identity; it is perhaps not too much to say another’s soul—was obvious in its sacredness,” he explains about neurosurgery. “Before operating on a patient’s brain, I realized, I must first understand his mind: his identity, his values, what makes his life worth living, and what devastation makes it reasonable to let that life end. The cost of my dedication to succeed was high, and the ineluctable failures brought me nearly unbearable guilt. Those burdens are what make medicine holy and wholly impossible: in taking up another’s cross, one must sometimes get crushed by the weight.”

In the book’s introduction, Abraham Verghese makes note of Kalinthi’s “prophet’s beard,” an idea his wife Lucy later clarifies as an “I didn’t have time to shave” beard—but to readers of his book, it’s clear that Kalinthi was, in fact, a prophet in many ways. His observation that “life isn’t about avoiding suffering,” which he acknowledges in his and Lucy’s decision to have a child despite his prognosis, demonstrates the ways he understands the world beyond his own life. Experiencing illness as a doctor—and a sensitive, empathetic one—adds a moral gravity to his words.

The Kalinthi family: Paul, Lucy, and baby Cady

Paul Kalinthi passed away surrounded by his family when his daughter Cady was eight months old. “When you come to one of the many moments in life where you must give an account of yourself,” he tells his daughter in the final paragraph, “provide a ledger of what you have been, and done, and meant to the world, do not, I pray, discount that you filled a dying man’s days with a sated joy, a joy unknown to me in all my prior years, a joy that does not hunger for more and more but rests, satisfied. In this time, right now, that is an enormous thing.” His life was cut too short, though his extraordinary accomplishments in his thirty-seven years might make you reevaluate how you’ve spent your time, what you’ve taken for granted, and how to leave an imprint as large as his. —Holly Schechter

HOLLY SCHECHTER teaches English and Writing at Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan. She graduated from McGill University with a degree in English Literature, and holds an MA from Teachers College, Columbia University. She is active at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, where she received excellent care as a patient, and in turn serves on the Friends of Mount Sinai Board and fundraises for spine research. Her piece "Genealogy" appeared in the Fall 2014 Intima.

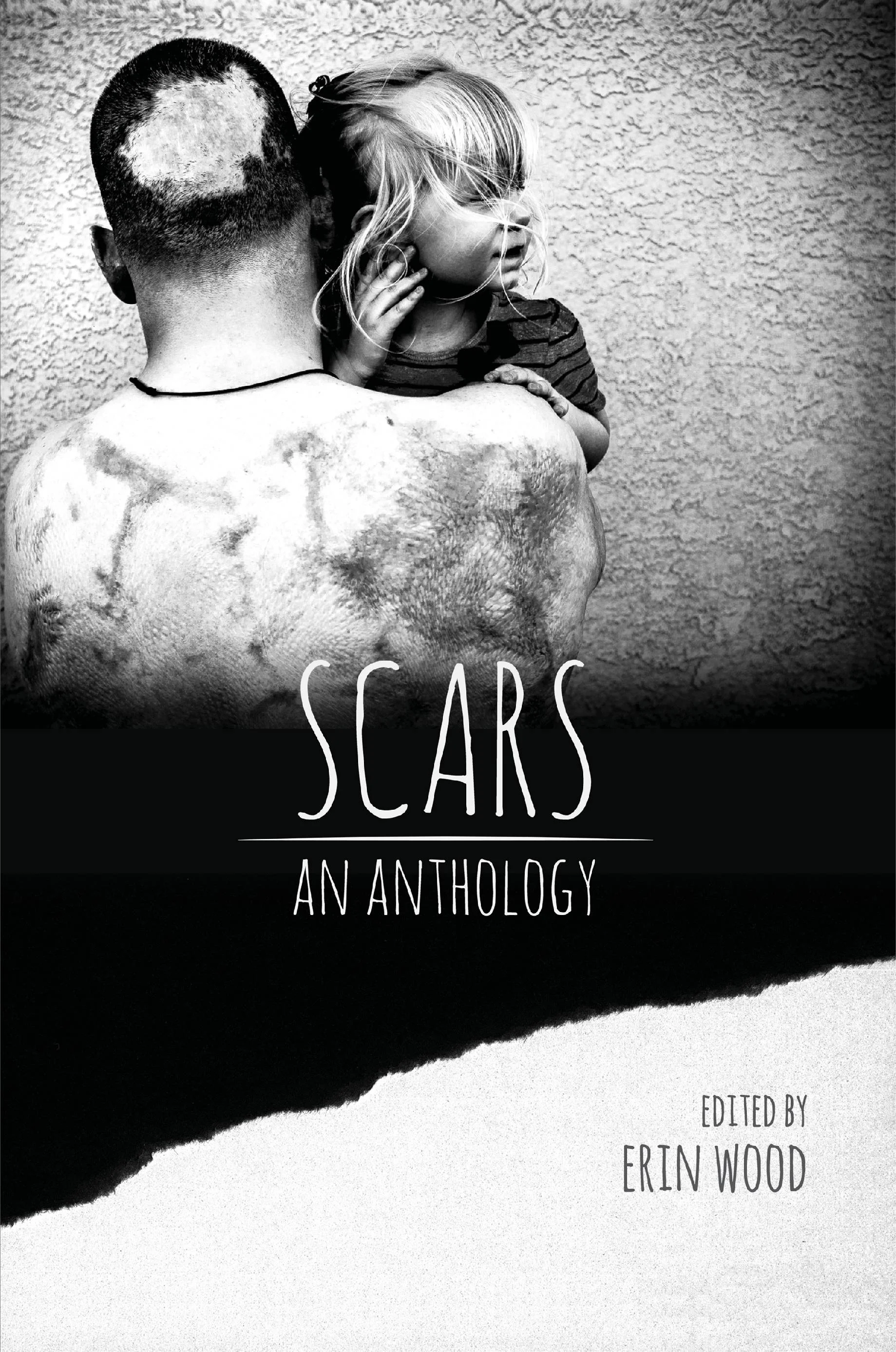

Scars: An Anthology. Edited by Erin Wood

For more on this book, go to www.etaliapress.com

For some two years, Erin Wood spent her time examining scars. As careful and probing as a surgeon, the writer and editor of Scars: An Anthology examined a wealth of poems, photographs, and prose about the subject and handled each person's revealing narrative with the emerging understanding that "there is a great deal about our scars that extends far beyond the individual body and the self."

Wood, whose essay "We Scar, We Heal, We Rise" was a Notable Essay in The Best American Essays 2013 (it appears in this volume) reflects on the ways scars may "belong to different versions of ourselves: our past selves...or new selves, selves in transition, or even selves we wish to regard more fully."

Stories that address these issues make the collection a rich reading experience that at times can be intense and painful, but also enlightening and entertaining. There is a lot of humor alongside the humanity that's revealed, as well as insight into the clinical encounter, most notably in Sayantani DasGupta's "'Tell Me About Your Scar': Narrative Medicine and The Scars of Intelligibility." One of the most moving and insightful pieces in the collection is "The Women's Table," an interview with Andrea Zekis, who speaks frankly about her "gender confirmation surgery" and the scars, emotional and physical, created but also taken away during her transition. A photo essay by New York photographer David Jay, who began The SCAR Project, is a stunning look at those who show their scars frankly and with pride. And while many of the pieces in this book are personal essays and memoirs, it is the poetry— like Samantha Plakun's "Written In Stitches" and Philip Martin's "The Pry Bar"—that draws the reader in close to examine the beauty and personal history revealed in the body's terrain.—Donna Bulseco

On December 10,2015, Columbia University's Seminar on Narrative, Health and Social Justice presented "Scars as Art, Text and Experience" at the Faculty House, featuring Editor Erin Wood and contributors Kelli Dunham, Lorrie Fredette, Samantha Plakun, and Heidi Andrea Restrepo Rhodes. Marsha Hurst, who is a lecturer in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University and co-chairs the University Seminar on "Narrative, Health, and Social Justice" introduced the panel. Hurst is co-editor with Sayantani DasGupta of Stories of Illness and Healing: Women Write Their Bodies. Listen to the event in its entirety below: