Disordered eating occupies a spectrum—anorexia nervosa at one end, morbid obesity at the other. Attempting rigid control of the body and its appetites, anorexics are unable to see themselves and their bodies accurately. Compulsive overeaters—often obese—similarly might not see themselves accurately. In both disorders, controlling food is the aim, a genuine addiction, a strategy through which addicts deal with the world and their own circumstances—a necessary coping skill, even though it is risky to health in both cases.

Read moreOn Bodies and Minds: A Reflection on Raina Greifer’s Artwork 'Bodies' by Diane Forman

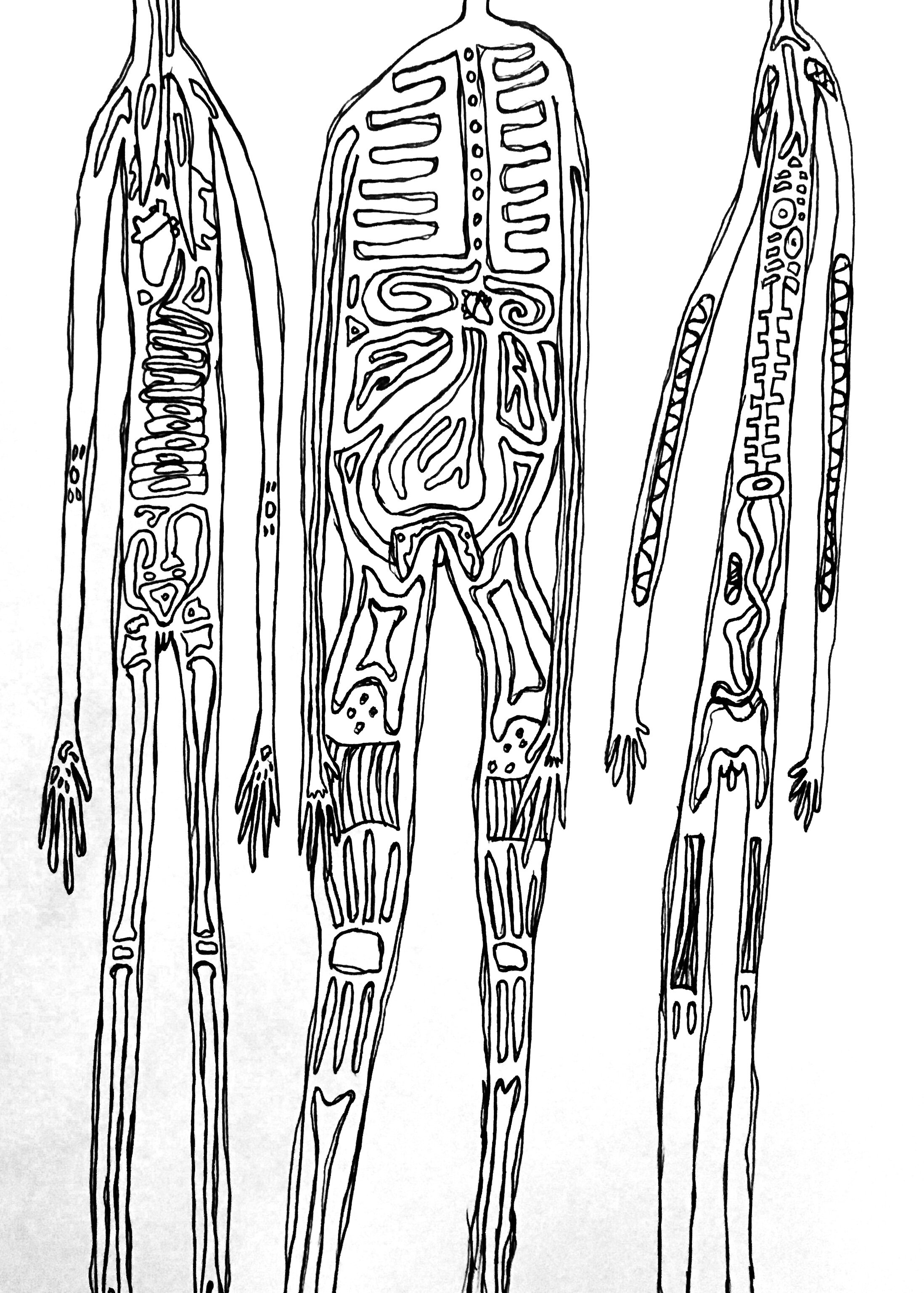

Raina Greifer’s artwork “Bodies” (Spring 2018 Intima) compels viewers to confront their own preconceptions and biases about body form. Her three headless, faceless bodies, of various sizes and depths, present a seemingly endless network of intertwined organs and bones, of breastplates and intestines and veins. Greifer urges the viewer to consider vulnerability, in the context of these drawings.

©Bodies by Raina Greifer. Spring 2018 Intima

Of course the body is much more than a composite of bones and organs, but a human cannot survive without the exquisite interplay of these parts. Greifer’s drawing asks me to consider not only the body’s intricate internal structure, but the external form shown to the world. Although the drawings are deliberately missing heads, the artist highlights the theme of vulnerability, which can only be contemplated through the integral component of the mind. Our minds magnify our vulnerability; our thoughts determine how we visualize ourselves, how we feel in our own skin.

After a lifetime of my own struggle with body dysmorphia, I was forced to confront both the mind and body’s strength and fragility when dealing with my daughter’s restrictive eating disorder, explored in my piece “Holding my Breath” (Spring 2020 Intima). Helplessly, I witnessed the ways in which the body fails without sufficient nutrition; how the body is reduced to conserving energy for the heart, brain, muscles, digestion. The body truly becomes a vessel of organs and bones all vying to survive.

But the starved mind is trying to survive too. Recovery is dependent on replenishing not only the organs with required energy, but the mind with recognition of the body's miracle and potential, whatever its size. I value Raina Greifer’s artwork, which encourages me to consider the vulnerability of the mind, and its intimate connection with the complexity of the body.

Diane Forman is a writer and educator. After a long career as writing tutor and educational consultant, Forman is currently working on a series of essays and a memoir. Additionally, she leads adult writing groups and retreats on the north shore of Boston. She holds a BS in English and Education from Northwestern University, and an Ed.M. from the Harvard Graduate School of Education and is an AWA affiliate, trained and certified to lead workshops in the AWA (Amherst Artists and Writers) method. Her non-fiction essay “Holding My Breath” appeared in the Spring 2020 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.

We Need More Stories From Young Patients by Kelley Yuan

Kelley Yuan will begin her studies at Sidney Kimmel Medical College in 2018 as part of the Penn State/SKMC combined BS/MD program. Her paper entitled "Stories from Kids: The Unheard Voices of Pediatric Patients" appears in the Spring 2018 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.

Thousands upon thousands of patient narratives. Remember the one from the eleven year old? Me neither.

We need more stories from young patients. They experience illness and emotions just as exquisitely as adults, if not more so. From their accounts we stand to learn a great deal about pain, hope and resilience. My piece, Stories from Kids: The Unheard Voices of Pediatric Patients, represents a small fraction of the many younger voices that narrative medicine has overlooked.

A great example of seeking youth voices is Ali Grzywna’s work, Anorexia Narratives: Stories of Illness & Healing. The accounts she gathered from anorexic teens and adults reveal how anorexia gave them a sense of control, a coping mechanism for other stressors, or a form of identity. Notably, she featured teen voices and the teen experience.

Based on this understanding of the underlying thought processes, therapy has evolved to treat anorexia. Instead of casting off the anorexic identity, patients learn to reshape the narrative to change their behavior—learning to select the healthy voice over the anorexic voice, instead of muting the anorexic voice altogether. Teen stories spurred progress.

Our current understanding of how children and adolescents interpret illness is dreadfully narrow, especially given the recent rise in juvenile autoimmune diseases and adolescent mental health issues. Without the youth perspective, our search for better treatments remains incomplete. The more we seek their stories, the more we can uncover to help these young minds and bodies heal.

Kelley Yuan will begin her studies at Sidney Kimmel Medical College in 2018 as part of the Penn State/SKMC combined BS/MD program. She studies illustration and fences épée when she should be revising for exams. Her work seeks to capture the rare, light-hearted moments in a field filled with pain, fear, and tough decisions. Her paper entitled "Stories from Kids: The Unheard Voices of Pediatric Patients" appears in the Spring 2018 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.